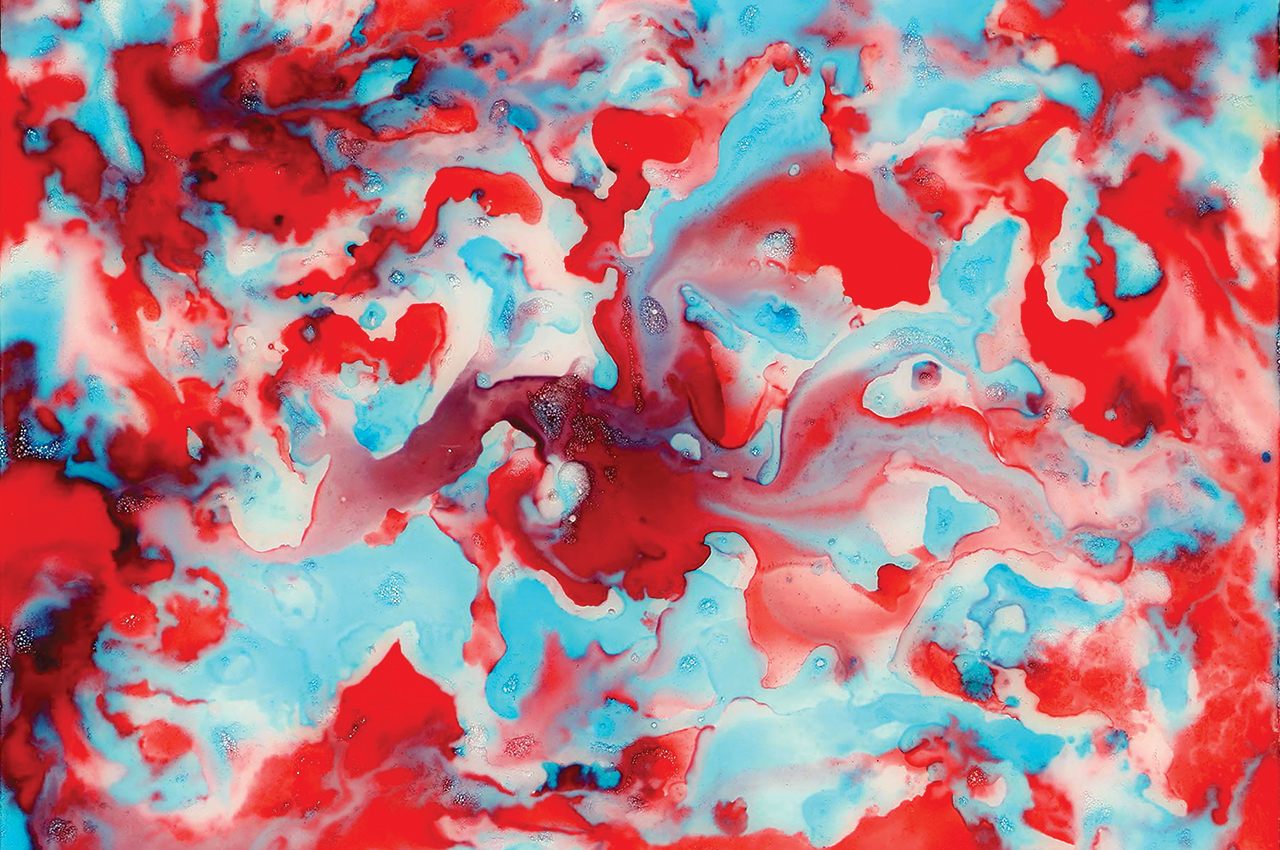

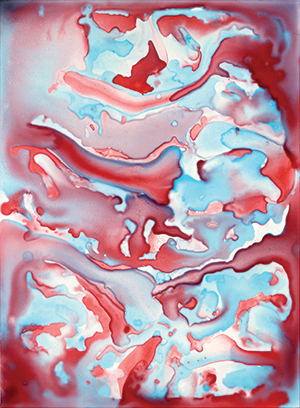

Above: Image: Matthew Drissell, “Blast of Fun” (detail), 2016; 37 3/8 x 28 inches.

Mixed media, including water, sugar, corn syrups, gum products and food dyes, on panel. See story, page 20.

Jones County

Little Fair Gets Big Names

Writer: Jane Burns

Some of the best music of the summer doesn’t require a trip to Bonnaroo or Lollapalooza. All it takes is a weekend in Jones County.

Each year in July, the Great Jones County Fair (greatjonescountyfair.com) in Monticello books a music lineup to rival any state fair or big-city concert venue. In 2019, performers included country superstar Tim McGraw,’90s hit-makers Hootie and the Blowfish, seven-time Grammy winner Chris Stapleton and contemporary Christian artist Toby Mac.

The fair began in 1853, and the big-time grandstand performances began a century later.

“We’re older than the dirt they perform on,” says the fair’s general manager, John Harms. “Performers know about us and know they’re going to have a good time. We’ve had agents and artists get in touch with us about coming to the fair.”

Newcomers and legends have come to Jones County, from 13-year-old LeAnn Rimes in 1997 to country queen Loretta Lynn (1975, 1977, 1980). The fair caught country star Miranda Lambert early in her career with a show in 2005, and she’s returned twice.

“We joke that we’ve added a zero to her paycheck each time she came back,”

Harms says. “And that’s true, going from $5,000 to $50,000 to $500,000.”

How does this one county meet such expenses when other fairs can’t? They use some of their gate receipts to supplement concert ticket sales. The musical acts in turn boost attendance numbers at the gate. Still, those artist paydays have sent ticket prices to the $75 range, but fans can also listen for free (after paying fair admission) on the hills by the grandstand.

“It’s the best of both worlds,” Harms says.

Brooklyn

Leap of Faith

Writer: Karla Walsh

Drive across Iowa on I-80 and you’ll encounter the World’s Largest Truck Stop and dozens of smaller ones scattered amid miles of rolling farmland. As you go past Exit 197, look up: No, you’re not imagining things—there are people floating in the sky.

Opened 26 years ago and purchased in 2015 by Kacie Boyd, Skydive Iowa (skydiveia.com) in Brooklyn helps more than 4,000 people each year fly like birds without stepping outside the state. You just have to be willing to step outside the plane.

“Skydiving is a fairly hidden thing here in Iowa,” Boyd says. “Most people don’t know it exists as an option in our state until they hear about it from a friend.”

Yes, you can skydive in Iowa. And yes, it’s safe.

“The technology in parachutes has blown up, and the safety features mean that even if we both pass out, the parachute will open and get us safely to the ground,” Boyd says.

Allow for half a day, not counting travel time, for the complete skydiving experience (just in case clouds roll in and there is a weather hold). Typically, training and jumping only takes 90 minutes when it’s nice out. Choose a jump at 14,000 feet, which includes 50 to 60 seconds of free-fall time, or a jump from 9,500 feet, which has a 30- to 40-second free fall. Both are followed by six to 10 minutes floating with the parachute deployed.

“A lot of Iowans jump with us, many of whom are college students new to the area. But we really see a wide variety of ages,” Boyd says. “Young people often skydive for the rush, while older people do it for their bucket lists. In the 11 years I’ve been an instructor, I’ve never had anyone not jump once they get inside the plane.”

So what, exactly, does it feel like?

“Skydiving is the ultimate sense of freedom,” Boyd says. “You can have everything wrong in your world, but the moment you jump, you will live in that moment and forget everything else.”

Sioux Center

37 3/8 x 28 inches. Mixed media, including water, sugar, corn syrups, gum products and food dyes, on panel.

Art Conveys Sense of Place

Writer: Suzanne Behnke

In the northwest corner of Iowa, rows of crops stretch to the horizon, interrupted by small towns or farms or clusters of cows.

These images of industrial agriculture feed Matthew Drissell’s inspiration to capture agriculture and sustainability in his artwork.

“I believe that it is important for artists to create mindful of place, considering where they live and how their work can be part of the conversations there,” he says.

The Dordt College professor of art and his family have lived in Sioux County for 10 years.

He finds that industrial agriculture and modern art overlap in some ways, and he is willing to explore ways to incorporate Sioux Center and its surroundings in his works—from Bomb Pops made by Blue Bunny in Le Mars to the windfall walnuts in his neighborhood.

“I found that by using unorthodox art materials, there are more conceptual possibilities with my work,” he says. “Also, by creating popsicle paintings, barn quilts or scenes of my neighborhood, I, too, am able to root my work in place, creating conversations within my community.”

He plans to keep exploring unconventional methods and inspiring viewers of his work to be mindful of place. “I am enjoying a shift to more natural materials like walnut ink,” he says. “I hope to continue that by discovering other natural inks and dyes, particularly those that have historic ties to the upper Midwest.”

North Liberty

Pressing On

Writer: John Busbee

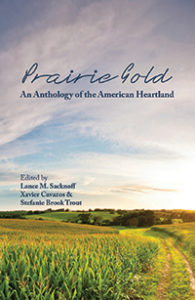

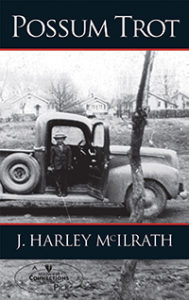

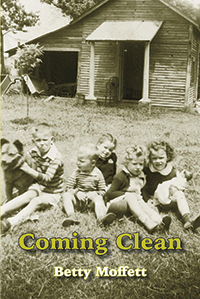

In an era when volatility and disruptive change have become the norm in the book publishing industry, Ice Cube Press not only has survived but continues to thrive. Since 1993, Steve Semken has published an eclectic array of titles through his North Liberty publishing company. Its catalog lures new readers and beguiles longtime fans with its founder’s eye for engaging literature.

Since his University of Iowa days, Semken always has been drawn to the written word, in all its forms. Today a versatile multitasker, he publishes six to eight titles each year.

“I was inspired to be a publisher because I was writing and writing and wanted to get more involved,” says Semken, the author of six books.

“I started with short stories and poetry, then began a small magazine called Sycamore Roots, then switched to publishing books. I’ve never had classes in writing, business, design or anything.

I’m kind of the quintessential autodidact.”

Adapting to trends in the publishing world, Semken has built a national network for distributing his books. Though widely ranging in styles, the titles embrace a unified voice.

“I use any format [or] style of writing that better explains how we can best live in the Midwest,” he says when asked about what genres he represents. “Poetry and memoir, history, crime fiction, photography”—they’re all part of the company’s offerings.

Now 55, Semken believes his legacy will be a record of finding and publishing “work that shows my … interest in both useful and odd qualities of living in the Midwest.”

In the process, he says, he has been grateful for the opportunity “to help authors reach their dreams” and for the realization “that people trust me with their writing.”

Iowa City

Captains Courageous

Writer: Mike Kilen

Harper Stribe stood midfield at Kinnick Stadium and unleashed a flurry of waves to the crowd before a football game in the fall of 2018. She had survived cancer, completing her treatment in May just across the street at University of Iowa Stead Children’s Hospital in Iowa City.

The crowd saw the sheer joy from this pint-sized 7-year-old from Polk City and unleashed a roar so long and loud it was as if the Hawkeyes had won on a last-second touchdown.

“For one day, they are a sports hero standing on the field and everyone is cheering for them. There’s a lot of pride and tears of joy in that moment,” says Cheryl Hodgson, the hospital’s director of marketing, who was part of a team that dreamed up the Kid Captain program 10 years ago. “That’s why I wear sunglasses no matter the weather. You get teared up every time.”

The partnership between the hospital and the Hawkeyes is a heart-tugging celebration of life that honors pediatric patients treated there. In 10 years, 134 children nominated by parents or guardians have been chosen to be captain for a football game.

In August, the children are given a jersey, take a tour of the stadium, meet players and coaches, and get to run out of the tunnel, just like the football players. On game day, the battle-ready players give them high-fives and fist bumps, and coaches pat their backs as they are introduced to the crowd, which hears their stories of courage.

“The kids get to come to Iowa City for something other than tests or procedures. It’s a day to celebrate life,” Hodgson says.

Videos of the children’s stories, produced by creative media manager Kaitlyn Busbee, are seen worldwide.

A Polish family learned more about treatments for their own child after viewing one. But Busbee says it’s also a chance for the children to tell their story to others for the first time.

“When you hear their stories it’s hard to fathom what these kids have been through,” she says.

The players feel it, too, and often tell of its deep meaning for them. That’s why 6-foot-4 Hawkeye Landan Paulsen bent down to whisper in little Harper’s ear before taking the field. “I’m feeding off your strength,” he told her.

Okoboji

A Noteworthy Museum

Writer: Larry Erickson

An Okoboji museum of note has more notes than most songs. They’re bank notes at the Higgins Museum, devoted to the history of national banking from 1863 to 1935.

The Higgins is one of several quirky museums in the Great Lakes area that specialize in narrowly focused categories. It includes purportedly the world’s largest permanent collection of the elegantly designed currency issued by national banks in Iowa and surrounding states. You’ll also see such banking artifacts as safes and a teller cage.

A bonus: You’ll find a great collection of Iowa postcards from a century ago.

Visitors on popular tourist websites praise the little museum. “It turned out to be fascinating,” noted one. Another: “A quirky place that I didn’t expect to find.”

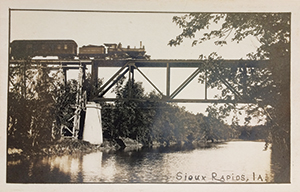

Other fun museums nearby include the Dickison County Museum, where the biggest exhibit is the building itself, a former railroad depot. More specialized are the Iowa Rock and Roll Association Museum, the Iowa Great Lakes Maritime Museum and Okoboji Classic Cars, where cars are viewed in elaborate, nostalgic street scenes replicating the Spencer, Iowa, of the creator’s youth.

Iowa City

Housing the Creative Spirit

Writer: Mike Kilen

Andrea Wilson wanted to move from her big-city corporate job to a place where she could write more. Her research produced a familiar result—Iowa City, 35 miles from her hometown of Columbus Junction.

Known for the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop and other University of Iowa writing programs, Iowa City was a perfect fit to write and open a bed and breakfast, which she did in 2014.

Wilson soon discovered the UNESCO City of Literature didn’t have a literary center devoted to writers, as nearly 100 cities across the country had, and believed her 1920 house would be a perfect venue for writing conferences and retreats. A year later, the Iowa Writers’ House (iowawritershouse.org) was born.

Instead of sitting under stark florescent lighting in a classroom, writers and editors, or those simply interested in literature, gather in the comfortable, historic home. “It feels a little like an old-time salon from a time when things moved slower and we listened to our feelings,” Wilson says. Writers “can focus on what is inside and put it to a page. It’s a gift to yourself.

“One in three people think they have a book in them,” Wilson adds. “But there is a need for education as a writer. You need to learn the craft together with the emotional output,” referring to the heart and soul that good writers express in their work.

Nearly 70 percent of the writers who attend instructional classes want to publish their work, while the others are hobbyists. Classes are led by experienced writers, such as students of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, or the likes of Rebecca Makkai, who was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize.

“Fabulous students from across the Midwest, a gorgeous old house, literary oxygen—l can’t recommend it highly enough,” Makkai says.

Visiting writers can book an upstairs room that holds the books of noted authors who have stayed there while in town to read at the famed Prairie Lights bookstore downtown, or take classes that incorporate other disciples, such as meditation, with writing.

“We are in the midst of a cultural renaissance, and people want to really experience more passion in their lives,” Wilson says. “They want to create and be surrounded by beauty.” ●