Above: Blocks of wood await the artist’s touch, to carve away everything that doesn’t look like a bird.

Writer: Mike Kilen

Jennifer Felton has hunted pheasants, ventured within yards of grizzly bears in Alaska, and cleared land to build an off-the-grid cabin with her husband, Todd, in the remote Iowa countryside.

“This is how I roll,” she says.

When she discovered woodcarving, she quickly took to another challenge—entering the male-dominated world of competitive wildfowl carving at the Ward World Championship Wildfowl Carving Competition in Ocean City, Maryland. She won the novice division. She followed with wins in intermediate and last year became the only woman to win in the decorative life-size wildfowl category in the advanced division.

In a relatively short 10 years of competition, Felton is on the cusp of a becoming a rare female master.

Felton, of rural Storm Lake, did it with the fearless heart of an outdoorswoman who studies the habits of birds in the wild and an artistic flair, born of an education at the Minneapolis School of Art and Design. She’s capturing attention from the world masters, who come from every state and eight foreign countries to compete.

Her barred owl (pictured, opposite page), which won the top prize overall in the advanced division and first for advanced birds of prey this past April, stopped even master Del Herbert of Chula Vista, California, who has penned books on the subject.

“The pose, habitat and attitude of the owl all said, ‘I’m king of all I survey; look at me.’ It’s just a beautiful piece, but also a commanding work of art,” Herbert says. Felton “shuns traditional patterns to develop her own designs and compositions. Her mastery of carving techniques and craftsmanship has freed her to concentrate on artistry and storytelling through her work.”

Birds of Prey

Entering Felton’s rural home, one meets the arresting figure of a life-size red-tailed hawk that she carved and painted.

“I like birds of prey,” she says. “I like the fierceness.”

Woodcarving is meticulous work. Each bird takes anywhere from 950 to 1,500 hours to complete. One mistake, one miscalculation of measurement of a single feather’s placement, could mean starting over.

That patience is hard-earned from way before the carving begins.

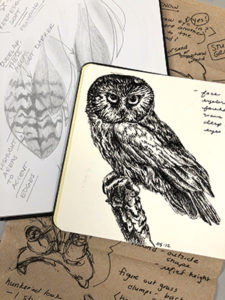

Felton spends long hours at both her cabin and the acreage watching how the raptors behave in the wild, taking photographs and making sketches. She doesn’t want just to replicate their look but to capture their behavior in her work, so she travels to a raptor rehabilitation clinic near Carroll to study them closely.

She’s even collected road kill to put out on the land and watch wild raptors feed, once seeing a rough-legged hawk and red-tailed hawk in a fight over food.

Capturing Habitats

It isn’t just a study of the birds, it’s also the habitat. Felton will collect leaves and branches to get the colors and textures of the habitat to create a lifelike sculpture, such as the sumac that her barred owl stands on. The red leaves are thin shavings of wood on branches made of steel.

Competitors must not only be carvers but expert painters and sculptors, working with the physics of creating a habitat for the bird to perch on. The best are also environmental experts, knowing the seasonal colors, biology and behaviors of the birds. That’s important because ornithologists are involved in the judging, says Kristin Sullivan, executive director of the Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art, which hosts the competition.

They don’t keep numbers on the growth of women in the competition, Sullivan says, but by mere observation it’s easy to see the increase from 50 years ago, when carvers at duck decoy competitions were almost exclusively men. Felton is still a rarity, with just one more win needed to achieve master’s level.

“I don’t want to be singled out. I want the work to win, not just because of my gender,” Felton says.

Felton always wanted to be an artist. “I had that dream,” she says. But her skills moved toward graphic arts and marketing for employment.

With the encouragement of family members, she started rough with only a small chain saw and created smooth, crude figures of birds. She dove into it quickly, getting better tools each year.

Meticulous Detail

Her artwork now fills a basement workshop, where she finds peace for hours as she carves the tupelo wood that is perfect for her work. There her barred owl perched regally last spring, waiting to be packaged for the competition.

Even down to its rictal feathers that look almost as thin as hair, each centimeter of the bird is carefully planned, carved and painted by hand.

“I want to make every pattern different because that’s the way they are,” Felton says. “I like to take the hard road; I like to earn it.

“The barred owl was difficult to paint, but I chose it for that very reason.”

The judges hover around the birds for hours as competitors stand at a distance, wondering what they are whispering to one another. Felton is mostly among men whom she has come to prize as friends, who warmly greet her at the bar the night before the competition.

After she captured a ribbon for the 10th year in a row, it was time to start conceiving next year’s contest entry. Meanwhile, her work is handled by a Rochester, Minnestoa, wildlife gallery, where some of her birds take flight for more than $60,000.