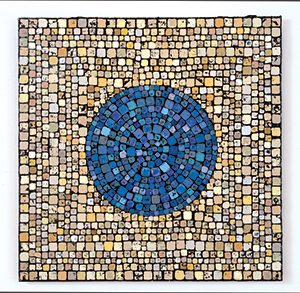

Bart Vargas, “Betrothal” (detail), latex paint on recycled wood.

Writer: Tim Paluch

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

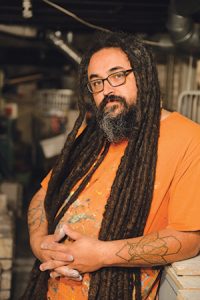

Bart Vargas is splashed with paint from beard to boots.

It’s a warm spring Sunday and the 44-year-old artist is taking advantage by working outside. With his long black dreadlocks pulled back in a ponytail, he’s hunched over sawhorses placed on tarps in the driveway of the Craftsman home he rents in Council Bluffs’ West End neighborhood, a stretch of long, tree-lined streets in the heart of the city’s flood plain.

The work is intense this weekend—he’s preparing artwork for two upcoming shows, both booked on short notice in the Omaha-Council Bluffs area. Then again, the work is often intense for Vargas, a relentlessly productive and prolific artist who works on multiple projects at a time, bouncing between mediums and aesthetics.

His creations use sustainable materials like reclaimed wood and discarded house paint, recyclables like plastic bottles, and e-waste like old computer keyboards. His art can be political, aggressive, comical. He sees his work as an artifact of modern life, an era of humanity with limited natural resources but infinite amounts of waste.

“Every piece of plastic you’ve ever had still exists in some form, somewhere,” he says. “When future civilizations dig this era up, they’re going to find a lot of Bronze Age artifacts—and broken plastic from us.”

Vargas has exhibited across the United States and in China, India and Eurasia; he opened his first solo New York show last April. All the while, he has remained a steady presence in the burgeoning Omaha-Council Bluffs cultural scene, mentoring high school students, teaching art at two local colleges and serving as a sort of shaman to young artists trying to make it like he did in the art world.

“Well, let’s go on inside,” he says, wiping his hands on the thighs of his pants. He stops on the steps to the side door for a few moments, before finishing his thought. “I don’t let a lot of people in here, usually.”

‘Organized Chaos’

Walking into the house, which serves as his studio now that he spends most nights with his fiancee in Omaha, is like unlocking a portal into the mind of the artist himself. The first floor is a colorful funhouse maze of pop culture artifacts, sculptures in various stages of completion and abandonment, tools, toys, boxes and bags of supplies, paint cans, and finished paintings—all piled together and narrowing the passageways between rooms. There’s even a stack of computer keyboards leaning against the oven. Art on top of art, buried beneath art, obscuring more art behind it.

“Organized chaos,” Vargas says. “And yes, I actually know where everything is in here.”

He speaks softly, contemplatively, offering anecdotes about items as he makes his way through the room:

There’s the 3-foot-tall white skull sculpture on a round table, abandoned at the moment because he hasn’t figured out the best way to make the bottle caps stick to it.

There’s the box of black computer keyboard keys, which showed up at his door one day, sent in the mail by a former high school classmate now living in Seattle.

There’s the clear acrylic sphere light fixtures sitting atop boxes of bottle caps, which he started pulling from the dumpsters of a local campus when the college converted all its outdoor lights to LEDs.

These spheres form the foundation of perhaps his best-known works: large globes created with old keyboard keys. He sold his first keyboard globe to a museum in Beijing in 2011, sold his second a year later to a private college in Pennsylvania, and in 2015 was hired by a museum in Azerbaijan to build one, on-site over 12 days, during the 2015 European Games.

Moberg Gallery in Des Moines, which has exhibited Vargas’ work and acts as his Iowa representation to corporate and private clients, recently sold another keyboard globe to a design firm in Manhattan.

“[The Manhattan buyer] is from Cedar Rapids and saw it in the window, and she said she couldn’t stop thinking about it,” says Ryan Mullin, Moberg’s gallery manager.

By most measures, Vargas’ career is already a success. He’s a full-time artist juggling a few art-related side hustles—teaching, mentoring, public speaking—who can now afford to keep a house as a studio.

Not bad for a military kid with a troubled past, he says. “I was the first person in my family to go to college. My dad dropped out of school in the eighth grade,” he says. “And I have had the chance to represent my country like eight times around the world.”

Young Illustrator

Vargas was born in 1973 on Offutt Air Force base south of Bellevue, Nebraska. His father was stationed in England soon after, and the family remained there for about three years before moving back to the Midwest. Early on, art was a hobby.

“I was drawing as soon as I could hold something in my hands,” Vargas says. “I drew and drew, filling one side of the paper, then turning it over and filling the other side.”

He hoped to become an illustrator, but youth turned to adolescence and he soon began to struggle in school—a D student, he says. Family life wasn’t much better.

His father was a complicated man, a Vietnam veteran struggling with his demons. There was alcoholism, violence and mental illness in the home. When Vargas was 16, he left and moved in with another couple, whom he still calls his “real family,” who offered him a bed.

“I was a confused, angry kid,” he says. When he graduated from high school, he served for six years in the National Guard, living and training in Texas, Colorado, Mississippi and Nebraska and spending time in Europe during the Bosnian conflict.

When he returned, he bounced from apartment to apartment, job to job, unsure of his footing in the adult world. He managed the shoe department at a Shopko store. He ran a machine that inserted junk mail into envelopes. He drove forklifts. He hung telecommunications cabinets on an assembly line for six months, until he got laid off. That’s when he took a job as a night janitor on the University of Nebraska-Omaha (UNO) campus in 2001 and finally started taking art classes during the day.

As a student, he quickly fell in love with color, painting and sculpture. He began painting on wood reclaimed from the school’s theater department sets, and diving into dumpsters for supplies for the types of sculptures—which blur the identities of garbage and waste by crafting them into universally recognizable forms—that would eventually bring him some measure of fame and recognition in the art world.

An early creation was a “bottle ball,” a spherical sculpture created with dozens of used plastic beverage bottles. Another, which took a year to make, was a basketball created out of bottle caps. These were the genesis of both his ideology on humans and waste, and also of his art process—a series of simple, painstakingly repetitive gestures that add up to become complex things. Much like cells and atoms and molecules—and also life itself, Vargas says.

“I could tell right away there was something different about him,” says Russ Nordman, a UNO professor who became friends with Vargas and who owns the home Vargas rents in Council Bluffs. “He practically lived in the sculpture studio, and he was making very ambitious things.

“It seems like you come around people who make art, and you can’t see them doing anything else except art. That was Bart.”

Art and Identity

Art and Identity

After earning his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 2007, Vargas enrolled at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities for graduate school. By then he was a decade older than his fellow students. Success began to find him—a feature in New America Paintings magazine in 2010 led to art sales and exhibition invites from across the world.

After grad school in 2011, he moved back to Council Bluffs and into the home he works in now. He started mentoring high school art students at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, and teaching art at the University of Nebraska and a local community college. He immersed himself in the art scene and his fledgling career. He showed his work in China, Greece, India, Mexico.

After his biological father—with whom he had no real relationship—died in 2005, Vargas began to think more about who he was, where he came from and what that ultimately meant to him. His father was a Mexican immigrant and his mother was a white woman from Michigan. He cut his 8-year-old dreadlocks as an “act of grief,” Vargas says. “The dreads were so symbolic of who I was, and I cut them as a kind of new beginning. I am the patriarch of this line I am on now.”

This thought stayed with him, and in 2013 he took a DNA test and illustrated the results in a series of long, narrow panel paintings of colorful bars he called “Registers.” He gave a TEDx talk on his discovery, focusing on identity, race, science and his art.

Later, he cut up those DNA panels and recombined them into smaller bursts of colorful rays, for a series called “Portals.” His debut solo show in New York City this past spring showcased these “Portals” paintings.

All the while, he kept creating, learning new mediums and producing new work at an impressive pace.

New Work

One sees evidence of this in his small attic, up a treacherously narrow and steep staircase. There, the floor and tarps covering tabletops are like accidental Jackson Pollock paintings, covered by six years’ worth of thick, hardened paint drips.

Up here this spring weekend he’s working on pieces of a massive installation for an August show at an Omaha gallery, where he will eventually mount as many as 400 small wood panels painted with stripes and squares of layers of house paint so thick it becomes an object and material as much as a color. The individual pieces are simple and striking, but when hundreds are placed together on a wall, the colors will dance together in a viewer’s eyes, Vargas says.

He recently taught himself slip casting, an old technique for mass-producing clay pottery and ceramics. Vargas built wood cottle boards to hold plaster molds of pop culture action figures— everything from “Star Wars” to King Kong to Marvel comics. He started mixing and matching the bodies and heads of these icons.

As he walks through his unfinished basement—somehow even more cluttered with art and supplies than the floor above—he points out a pair of “Star Wars” storm troopers with Mickey Mouse heads. “I wanted to show how Disney started buying up my youth,” he says. Marvel comics, “Star Wars” and more—all recent additions to the Disney corporate machine.

“For like six months I made crap,” Vargas says. “I wasn’t sure where it was going to go.”

Then Donald Trump won the presidency.

Vargas, not alone in the art community, felt angry and disillusioned, and decided he needed to make some sort of statement with his art in response to what he saw as a president embarrassing the nation on a global stage.

He bought baby dolls from local thrift stores, and ordered Trump bobbleheads, creating plaster molds of both so he could combine a clay Trump head with a clay baby doll body. His plan is to create at least one “Trumpling”—glazed in various shades of orange—for each day of Trump’s presidency, then create a massive wall installation of hundreds of angry, tantrum-pitching baby Trumplings this November at an art gallery in Omaha to commemorate the year since Trump’s election.

“He’s the sorest winner we’ve ever experienced,” Vargas says. “I think the installation will be powerful, documenting the screaming tantrums of a miniature man.”

Vargas plans to sell the Trumplings for about $100 each,

giving 75 percent of the proceeds to nonprofits affected by the administration: Planned Parenthood, American Defamation League and a local refugee relocation program.

The process of making a daily Trumpling—each small doll-sized creation needs six specific parts—was already wearing him down about 80 days in. Art is drawn from emotional depths, he knows, and those depths are seldom deeper for him than now. But, he notes, “this reminds me that artwork is mostly ‘work.’ ” And Bart Vargas sees that he has a job to do.