Above: Randy Richmond enjoys photographing (and trout-fishing) the spring-fed streams in northeast Iowa. This image is a stream flowing into Big Mill near Bellevue, which is protected by the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation. “The Iowa Driftless is a fragile region worthy of protection,” he says.

Writer: Kelly Roberson

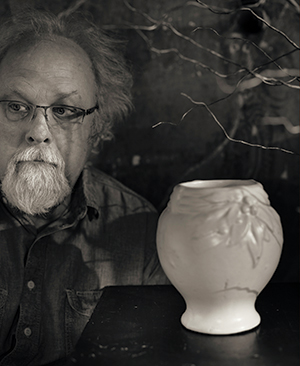

In his Driftless series, Randy Richmond trains his camera lens on a corner of the Midwest left mostly untouched by glaciers. His images capture layers of nature’s quietude, everyday spots—a bend in a creek, an undisturbed stand of a few conifers—that we’re disinclined to notice.

The prints are both historic in their execution—a selenium print process—and thoroughly modern, executed with digital photography. They’re also representative of Richmond’s career: a random collection of fortuitous moments that add up to a serious statement about what it is to create art right now.

“I didn’t have a plan,” says Richmond, 58, who lives in Davenport. “I didn’t have a list of things to accomplish to get from point A to point C. I didn’t care what people liked or didn’t like. I came into contact with people that also believed in what I was doing and liked what I was doing, and they were the right kind of people to push me forward.”

Most artists struggle for attention at some point in their careers; Richmond’s fight to be noticed began much earlier in life. His was a crowded household—he was the fifth out of six children growing up in Muscatine—and he escaped first on a bicycle as a teenager, regularly riding 100 miles on weekends. He went next to the University of Iowa, where he picked up the camera.

“While I was a college student, I became obsessed about learning about art—I would spend long afternoons in the art library pulling out photography books,” Richmond says. “That was a huge part of my education.”

He began experimenting with photography between long shifts at a hot dog cart. “One summer, I worked until 2 a.m., then I’d go home and sleep until 7, then get up and start on a photography assignment I gave myself,” Richmond says. “I did a lot of self-exploration, a lot figuring out how to communicate with the camera.”

Living Lean

The combination of Richmond’s upbringing—a crowded house, limited resources—and his internal motivation provided a helpful guide during the evolution of his decades-long career. Full-time father to his daughter after a divorce, he was well practiced at living lean. When digital cameras became widely available, he resisted at first—staying true to his large-format camera that shot 8×10 film—but the cost became too much.

“I learned how to create a feast on under $10 and we lived incredibly cheaply,” he says. “But I had to reinvent myself, and that dreaded word ‘digital’ had to be addressed.”

When he first embraced digital, Richmond would arrange things on a scanner, remove a background, and combine it with other things. His viewpoint began to garner notice by museum directors, show organizers and gallery owners.

“Randy’s work has a fascinating combination of intelligence, technical mastery and homage to photographic tradition,” says Susan Watts, owner of Olson-Larsen Galleries in West Des Moines. “It has a certain grace as well.”

Carolyn Levine of Muscatine has known Richmond for more than 20 years. “What intrigues me about Randy’s work,” she says, “is what he brings to the world of art–work that incorporates subject, process and paper in ways which are current and historical but completely new and creative.”

Nature Morte

That approach is clearly evident in his recent still-life, or Nature Morte, project (see images on page 103), which Richmond calls “the most important thing I’ve done.” All his previous work was “either practice or problem-solving or research that landed in this project.”

The striking still lifes, which were the subject of a 2019 six-month solo exhibit at Davenport’s Figge Art Museum, incorporate different genres of art history: the Nature Morte paintings of the northern Renaissance, the dramatic lighting of Neoclassical portraiture, and the soft focus of the Pictorialist photography of the early 20th century.

“The still lifes are actually staged, arranged and photographed outside, but they are lit as if they were in a studio using portable flash equipment,” he explains.

The stories depicted in the works are based on “what I see happening in the world today,” Richmond says. “The art history I use to present these stories indicates that a lot of these issues I illustrate have been going on for years and are the fruit of seeds that were planted decades and even centuries ago.”

The project stemmed from Richmond’s observation that “photography was getting weighed down by too much technology too fast. I wanted to slow things down and see if I could get people to look back over their shoulders to see what possibilities we might have missed.

“I believe that the still life … has always been a great vehicle to express ideas in a quiet way,” he adds.

Teaching and Learning

Richmond’s patchwork career now includes teaching at St. Ambrose University (he’s the school’s art studio technician) and photography. He still relies on his old habit of giving daily assignments. “I have my cameras out every day and I work every day—I treat myself as an employee,” he says.

Most of his most notable works are digital photos, turned into a high-resolution negative, then printed by hand onto handmade papers. It’s an unruly process, he says, but one that offers up rich, inky shadows and details.

Richmond’s work reflects the ruminative nature of his life, the quiet that was almost a requirement of his youth. His photography lets him speak, and that has perhaps saved him. “I discovered there were things I could talk about but not actually say. There were things that needed to be addressed from the quiet fifth kid that I could address visually without telling somebody,” he says. “Being able to speak without words became an important thing.”

In his “Blue Jays” image from his Nature Morte series, Richmond explores perceptions of other people, groups and cultures based on fiction. Here, he studies the blue jays’ reputation as noisy bullies due to their eating of eggs from other bird species. In fact, this rarely happens in nature.

In his “Blue Jays” image from his Nature Morte series, Richmond explores perceptions of other people, groups and cultures based on fiction. Here, he studies the blue jays’ reputation as noisy bullies due to their eating of eggs from other bird species. In fact, this rarely happens in nature.

“Swan,” from the same series, highlights the restoration of trumpeter swans in the state.