Above: Denise O’Brien isn’t one to shy away from digging in, whether it’s to uphold a political position

or to care for the organic produce on her farm.

Writer: Jane Schorer Meisner

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

Long-haired and strong-willed, throngs of Vietnam war protesters congregated in California in the early ’70s. They scattered when the conflict ended, and one became an Iowa famer.

Nearly 50 years later, she’s still an activist.

Former war protester Denise O’Brien and her husband, Larry Harris, operate Rolling Acres Farm northwest of her hometown of Atlantic. Their farm produces only organic crops, so she’s more focused on selling $5-a-pound nettles for sushi restaurants than on harvesting corn or soybeans.

“I’m a progressive liberal person,” says O’Brien, 67. “I have a lot of history behind me that makes me legitimate in that way.”

That history includes directing the Rural Women’s Leadership Development Project of PrairieFire Rural Action Inc. in the 1980s. In 1995, she participated in a World Women’s Conference in China, focusing on the globalization of agriculture. In 1997, she co-founded the Women, Food and Agriculture Network (WFAN) and spoke before the United Nations General Assembly on behalf of farmers.

In 2000, O’Brien was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2006, she narrowly missed being elected Iowa secretary of agriculture. From 2011 to 2012, she was a USDA adviser in Afghanistan. Along the way, she lobbied with the Iowa Farm Unity Coalition and served as president of the National Family Farm Coalition.

O’Brien calls herself a farmer—not a farm wife—although she knew nothing about farming while growing up in town with her seven siblings.

“My dad was a hunter,” she says. “I think my love for the outdoors came through him taking us squirrel and duck hunting.”

As a teen, O’Brien lived in Japan for a year as a foreign exchange student. There, she broadened her political perspective, especially after meeting Quakers who were secretly running supplies to North Vietnam at the height of the military conflict.

Back in Iowa, she spent a semester at the University of Iowa and then moved to Omaha for a semester at Creighton University.

“Then the next semester, I ran away to California and was part of the Vietnam protest,” she says.

focus is on the future, through stewardship of nature and the direction of our culture.

“The guy I was with at that time was a war resister, so we did a lot of activities in the San Francisco Bay area. Then we moved into a commune that was going back to the land.”

When the conflict ended, the couple traveled in an old panel truck to settle in Vermont. After several years away from Iowa, O’Brien came back to Atlantic—minus the guy—to care for her ill mother. That’s when local farmer Larry Harris introduced her to another type of activism.

“Larry and I were married six months after we met,” O’Brien says. “That was 42 years ago. Meeting him, falling in love and being here on the farm—I knew that my life couldn’t have taken a better path.”

The Harris farm had been in Larry’s family for generations, and Larry, an environmental activist, wanted to create an organic farming operation. Novice farmer O’Brien was all for the idea.

“Larry was a good teacher,” she says. “He showed me how to run the tractor and fix the equipment.”

The couple raised their three children in the same farmhouse in which Harris grew up. O’Brien calls the first few years on the farm “an apprenticeship” that prepared her for transitioning from Vietnam activism to farm activism.

During the 1980s farm crisis, O’Brien and Harris felt compelled to take action.

“We decided he would take care of the kids, and I would go on the road to be the activist,” O’Brien says. “It was never a point of contention about me being gone.”

Among other issues, O’Brien wanted to dig deeper into women’s roles in farming, especially because women own 50 percent of the farmland in Iowa.

“Denise did a great service to Iowa and to agriculture by founding WFAN, an excellent educational and networking group for women farmers and landowners,” says Mary Swander, co-founder and executive director of AgArts and artistic director of Swander Woman Productions.

Swander says O’Brien was a role model for women in running for Iowa secretary of agriculture—traditionally a male political position—and she continues to provide perspective on agriculture in Iowa and the United States. “She knows all the facts and statistics, as well as the social justice issues involved,” Swander says.

Today, O’Brien remains in demand as a speaker on topics ranging from women and agriculture to organic agriculture, sustainable living and food security. But mostly she devotes herself to growing chemical-free fruits, vegetables, herbs and flowers, plus antibiotic- and hormone-free turkeys and chickens, for individuals and restaurants in western Iowa and Omaha.

She also attends workshops and pores over books to learn more about organic farming. “Our farm has always been like an outreach in education,” she says. “I’m learning a lot and try to apply new techniques to farming.”

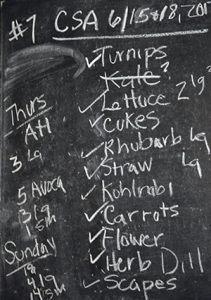

O’Brien served as a WFAN-designated mentor to Amber Mohr, a farmer and co-owner of Fork Tail Farm near Avoca. Now the two women work together in a community-supported agriculture (CSA) business.

“I admire Denise’s passion and dedication to all her endeavors, and she truly loves learning new techniques and trying new challenges,” Mohr says. “She cares deeply about our world, humans and the environment, so her activism truly comes from her inner spirit.”

Other area farmers identify O’Brien as “the mother of sustainable agriculture,” Mohr says. “Newer farmers are beholden to her for laying 40 years of groundwork promoting local foods, because thanks to those efforts, we have a local food market to sell within.”

O’Brien acknowledges that farming is physical work, with few days off. “And when I say ‘off,’ I mean I work at a slower pace those days,” she says.

Still, she’s grateful to be doing work that is enjoyable to her.

“I’ve always felt privileged,” she says. “When I go to meetings and stay in hotels for days, I can come back here and work in the orchard or outside and just give my thoughts to the universe.”