Above: Photographer: Ron Maggard

Clear Lake

Coloring the Winter Wind

Writer: Michael Morain

On the third Saturday of February, a kite festival spatters like paint across the blank-canvas sky over Clear Lake. Pull off Interstate 35 and head west into town to see the flecks of color grow into discernible forms—an orange octopus, a Chinese dragon, a yellow whale longer than a pair of school buses parked end to end.

There are hundreds of kites in all, tugging at tethers in the frozen lake. And there are thousands of giddy visitors, shuffling around on the snow-plowed ice.

Organizer Larry Day and his wife, Kay, founded the annual Color the Wind festival more than 15 years ago and have watched it grow far bigger than they ever expected. The event often doubles the town’s population of about 8,000.

Friends and neighbors plow the ice and drill holes for the kites’ anchors. A DJ shows up to play music, and volunteers help kids craft their own kites at the Clear Lake Arts Center.

But it’s the “kite people” who really make the magic. They come from all over, parking their trucks on the ice and unpacking trailers of gear. A stunt team called Fire and Ice choreographs precision kite-flying routines, somehow without getting their lines tangled. Kite surfers zip back and forth away from the crowd, as fast as the wind can pull them.

The weather can be bracing, to say the least, but few people seem to mind. A trio of pandas, a scuba diver and a school of tropical fish, a pig with wings—everywhere you look is another marvel, dancing in the sky.

“I don’t care if you’re 3 or 93,” Larry Day says. “It’s peaceful, it makes me smile—and it’s fun.”

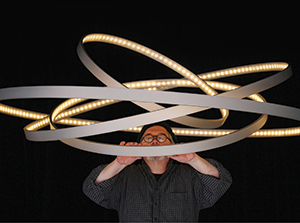

Elkader

Light Duty

Light Duty

Writer: Annette Juergens Busbee

Suspended over a spa in the Four Seasons Hotel in Baku, Azerbaijan, is a light fixture shaped like a giant cloud, 60 feet long and 15 feet wide. In a new rec center on the Louisiana State University campus in Baton Rouge is a 100-foot-long lighting installation called “River.”

Both were designed and created at Fire Farm, a custom lighting company in Elkader, a town of 1,200 people in northeast Iowa.

Products developed by Fire Farm can be found throughout North America and Asia. The company sells its custom lighting primarily to interior designers and architects working in the hospitality and other commercial markets.

Founder Adam Pollack says he tries to create lighting that is functional but also artistic and sculptural, experimenting with materials and techniques not normally associated with lighting to see how the light is affected as it passes through. Pollack and his staff discovered that introducing smoke in the powder coating process results in a striking ombré finish on metal, and he has recently started working with felt.

The company also strives to ensure its products set the appropriate tone for the spaces they are designed for. “Lighting should help people connect to the environment,” Pollack says. “It should tell the story of what’s going on in that space.”

Like the one told as part of the expansion of a Madison, Wisconsin, church designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Fire Farm designed wall sconces using copper strips from the original roof. The side that had been exposed to years of weather had a beautiful patina, while the unexposed side remained a bright, shiny copper.

“We wove the two sides together to symbolize the joining of the original church with the new addition,” Pollack says. “It’s very simple, but the design tells a meaningful story.”

Massive projects that involve many large pieces of different designs can run hundreds of thousands of dollars, but much of the work in a smaller 2- to 10-foot scale is priced between $1,000 and $15,000.

Before starting Fire Farm, Pollack developed theater stage lighting and illusions with light in the San Francisco area. He established Fire Farm in 1991 in Oakland. In 2001, he moved the company to Elkader near his wife’s family.

“I feel very blessed,” Pollack says. “I have a talented team and this playground I get to explore in every day.”

Orange City

The Beauty of Ritual

Writer: Jane Schorer Meisner

Artist Yun Shin of Orange City finds meaningful bits of inspiration tucked within the packages she receives from her home country of South Korea. The boxes, frequently sent by her parents, provide important links to home.

“The packages always arrive with a packing slip with one of my parents’ signatures, which is very familiar for me,” says Shin, a 2016 Iowa Arts Council Artist Fellow and assistant professor of art at Northwestern College. “Also, there are multiple copies of the slip, which is fascinating to me with the way the signatures are filtering all the way through the different layers.”

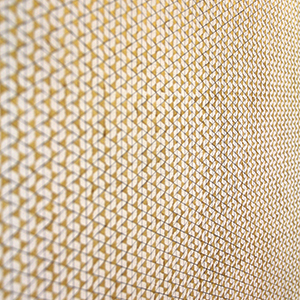

Shin, a 41-year-old who has exhibited in solo and group shows throughout the United States, uses minimal materials—sometimes as little as pencil and paper—to create two-dimensional artwork that often involves repetitive tracings of the same shapes, including her parents’ signatures.

“My work is all about process,” Shin says. “It involves ritual, repetition, process and a demand for contemplation.

Living alone in a foreign culture, the sense of longing predisposes me to practice simple activities daily.”

To create her work titled “IMG I,” Shin spent six months tracing her mother’s signature. “To me, it is a way of reconstructing relationship and remembering home,” she says.

For “Sheet,” a 90-by-66-inch work, Shin spent nearly a year recreating a pattern that her mother had crocheted to create a queen-size bed sheet.

“I drew vertical and horizontal lines on paper with graphite, evenly every one-eighth of an inch,” she says. “Then I started dotting every other intersection with oil paint. Viewers see only the abstract and translucent pattern of dots, which is on the back side of the paper created by the way oil saturates through it.”

Shin earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Chosun University in South Korea in 2000, then moved to the United States, where she earned a bachelor’s degree from Virginia Commonwealth University and a master’s from the University of Texas at Austin. Soon after, she was hired at Northwestern College, where she teaches courses in painting, drawing, sculpture and ceramics.

“I used to work three-dimensionally when I was in college and grad school,” she says. “Teaching painting and drawing has influenced me to move on to a two-dimensional surface. I want my students to know that art-making requires patience and that each stage of the creation process is very important and has meaning.”

People sometimes find it difficult to wrap their heads around the time Shin invests in each piece of art, says Phil Scorza, chairman of the art department at Northwestern.

“Her work is deeply personal, and hidden to most is the unrelenting focus and work ethic given to each piece, which seems to be more ritualistic or meditative than an artistic endeavor,” Scorza says. “The visual result of this silent investment in her art is powerful.”

Dubuque

Growing a Community

Growing a Community

Writer: Sophia S. Ahmad

Husband and wife team Mike Muench and Leslie Shalabi of Dubuque share a belief that the world needs more human connection.

“We wanted to use the idea of food as the vehicle for creating that connection,” Shalabi says. “I like entertaining and that special thing that happens around the dinner table. I wanted to recreate that feeling in a large way.”

After retiring from their positions as partners in an insurance company (Muench) and an international public relations firm (Shalabi), they opened Convivium Urban Farmstead—a privately funded community and campus built around food—in the city’s North End neighborhood. Events and programming envelop the entire food cycle: growing, harvesting, preparing, enjoying and composting.

The couple chose an old greenhouse and nursery in the middle of a dense urban block for Convivium, a Latin word for “feast.” The 13,000-square-foot property opened in March 2017 and includes a coffee shop, training kitchen, event space and learning center.

Experiences there are integrated. Local community college students chop vegetables in the training kitchen, which are then frozen and used in the soups and quiche served in the coffee shop.

The learning center hosts classes for planting seeds and creating composting bins. Past dining events included a Dinner in the Dark, during which blindfolded diners explored cuisine by heightening their nonvisual senses, and a Middle Eastern Night, which included multiple family-style small-plate courses.

Future plans include completing an aquaponics area (a symbiotic environment for raising plants and fish, mollusks and other aquatic animals), as well as an indoor permaculture orchard. As of press time, the couple planned to list on Airbnb the space above their garage adjacent to Convivium, so visitors can enjoy a weekend-long foodie experience.

Loess Hills

Lavender Fields Forever

Lavender Fields Forever

Writer: Jane Schorer Meisner

The inspiration for Mary and Tim Hamer’s Loess Hills Lavender Farm near Missouri

Valley was a fragrant 8-acre field they visited in Washington state in 2005.

Mary, then a computer programmer and lay pastor, was so taken with the lavender that she started plants at her Chariton home to see if they could survive in Iowa’s climate. Soon she and Tim, a bank trust officer, purchased a 13-acre farm north of Missouri Valley, near where both grew up. Relatives and friends helped plant rows of lavender there, about 1,200 plants in all. They constructed a gift shop and assembled a kitchen for making balm and lotion.

“I first thought I would just take bouquets to farmers markets,” Mary says. “That quickly changed, and the farm took on a life of its own.”

Now, thousands of visitors trek to Loess Hills Lavender Farm each year to meander the paths, view (and sniff) the fragrant flowers, cut bouquets and linger in the gift shop, which sells Mary’s homemade lavender products along with items from 40 local artists and vendors.

The farm has become a popular wedding venue, with rows of plump purple tufts gracing a backdrop of lush rolling hills.

“People come from all over the world to see our little town because of this farm,” says Annette Deakins, executive director for the Missouri Valley Chamber of Commerce. “Everyone who comes to see it raves about what a wonderful gem this hidden treasure is.”

On designated days, visitors can enjoy American high teas, learn to make lavender wands or other crafts, and sample lavender cookies, lavender lemonade and lavender fudge. A festival called LavenderStock is held the third Saturday in July, during the farm’s peak blooming period.

Okoboji

A Trip Back In Time

A Trip Back In Time

Writer: Terri Queck-Matzie

The Ultimate Man Cave is in West Okoboji: 88,000 square feet of automotive immersion, a trip back in time to when road machines ruled.

Longtime car collector Toby Shine opened Okoboji Classic Cars in 2013 as a showroom and full-service restoration shop. Things took off from there.

Today, a 28,000-square-foot mural and indoor dioramas, painted by local artist Jack Rees, recreate how Grand Avenue in nearby Spencer and Arnold’s Park amusement park looked in the mid-1960s.

This works as a backdrop for 87 classic vehicles displayed around the main museum showroom. Period furnishings and collectibles fill the storefronts of Woolworth’s, Lunch Drug and of course the local Buick dealership, while guests relive the view of Lake Okoboji from the Arnold’s Park midway with its iconic Ferris wheel.

The Arnold’s Park Event Center provides space for special events and includes a working drive-in theater that plays era-appropriate films such as “Goldfinger” and “American Graffiti” during tours.

Cars from Shine’s personal collection, ranging from a 1915 Studebaker to a 2015 Dodge Challenger Hellcat, line the street in front of the shops.

Shine built Okoboji Classic Cars as a place to store his collection under one roof. But as more people requested to see inside, he eventually opened the doors to the public.

“It’s something different, a diversion that’s fun,” Shine says.

Quad Cities

A Music Goldmine

A Music Goldmine

Writer: Chad Taylor

In 2006, Quad Cities native Sean Moeller had an idea: Record intimate studio sessions with independent musicians, giving fans a personal, unpolished look at some of their favorite artists.

A dozen years later, his idea, Daytrotter, is a nationally known indie rock institution based in the Quad Cities. Moeller left Daytrotter in 2016, but his concept has continued to grow, churning out as many as 60 songs from more than a dozen bands every week, from up-and-coming bands to Grammy winners and big names like Wilco, Glenn Campbell and Carly Simon. Daytrotter now has a mobile app—made in conjunction with Paste Music—and a 375-seat live music venue in Davenport, which opened in January 2016.

Songs are recorded analog rather than digitally, with no overdubbing or edits allowed. Once released on the website, tracks are accompanied not by a slick press photo, but by Johnnie Cluney’s striking, quasi-minimalist illustrations of the artists, originally done in watercolor, now mostly drawn with pen and marker.

But even as the profile of visiting acts continues to grow, keeping that connection to bands from Iowa and the Midwest who were a part of Daytrotter’s initial success is equally important to Cluney and the rest of the team.

“Sometimes we’re on our conference call for the weekend and someone will ask, ‘Why did this band only get a couple hundred views?’ ” Cluney says. “Well, if it’s the type of band that we believe in, even if they only have 200 fans now, they’re going to have 2,000 in a few months.”

It happens. New York rock band Vampire Weekend played a Daytrotter session on its first tour in 2007, before going on to score a pair of Billboard No. 1 hits and taking home a 2014 Grammy.

“That’s the beauty of [the Daytrotter sessions],” Cluney says. “There’s a Grammy winner sitting right next to some band you heard in someone’s basement.”

Des Moines and Orient

Living Traditions

Writer: Terri Queck-Matzie

The Wallaces, considered America’s first family of agriculture, built their reputation on bringing people together over food and farm. Today that proud tradition continues at the Wallace Centers of Iowa’s two locations.

“Everything relates in some way back to the foundation laid for us,” says Ann Taylor of the Wallace Centers. The family, including ag entrepreneur Henry A. Wallace—former vice president of the United States, secretary of agriculture and secretary of commerce—believed in strong communities, the interdependence of rural and urban areas, and the value of bringing people together in conversation to solve problems.

The Wallace House in Des Moines’ Sherman Hill neighborhood is the restored 1883 Victorian home of the Wallace family. Here, Henry A. Wallace’s grandparents, Henry C. and Nancy Wallace, made their home and entered the farm publishing business.

The house is now home to farm-to-table dinners, civility lunches, women’s leadership lunches, and Hearts and Homes Historic Teas events. All feature programs that are designed to inspire civil dialogue about current issues while food fresh from the farm is served.

“It’s neat because that’s the kind of gathering and conversation that used to take place there,” Taylor says. The intimate setting that can accommodate 20 to 25 people helps foster networking among the guests and with the speaker.

The 40-acre Henry A. Wallace Country Life Center near Orient marks the birthplace of Henry A. Wallace and pays homage to his lifelong dedication to agriculture and rural life.

Today at the 40-acre farm, a Gathering Barn provides a modern space for business meetings and conferences as well as private gatherings. You’ll also find 12 acres of produce gardens and orchards, along with native prairie outdoor art installations and walking paths.

On weekends through the summer, the Gathering Barn’s restaurant serves a menu created with produce fresh from the garden. The gardens also supply produce for subscribers to the Wallace Center’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program.

“Economically and culturally, we try to make a sustainable difference in our communities,” says Taylor. “We’re always looking for meaningful ways to connect our past with the present and the future.”

Jefferson

Forging Ahead in Rural Iowa

Writer: Kellye Crocker

When Pillar Technology opens its newest office in spring 2019, bringing high-tech jobs to downtown Jefferson, a north-central Iowa city of 4,345, there may be only a few employees. But the facility is just an early step of an ambitious attack on rural Iowa’s brain drain, and the company plans to “grow” its own team.

“A tsunami of a movement starts here,” says Pillar’s Linc Kroeger, who has the title of “vanguard of Future Ready Iowa.” (He also serves as an ambassador for Future Ready Iowa, a separate state initiative.) “I do expect there will be more [offices] in Iowa—or we wouldn’t be doing this one—but we have to learn from this first.”

Pillar was founded in 1996 and employs more than 300 people in its Columbus, Ohio, headquarters, plus modern, open floor-plan offices in downtown Des Moines; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Palo Alto, California. Along with offbeat job titles such as vanguard—defined as leading the way toward new ideas—the company calls its offices “forges” and emphasizes an industry-disrupting ethos.

The technology and software firm has created software for driverless cars and for smart tractors that know the precise angle at which a seed should be planted for optimal harvest. The company also has developed a more efficient, money-saving meter-reading system for a large energy company.

Greene County voters twice rejected school bond proposals in recent years, but last April overwhelmingly approved a $21.5 million bond issue connected to the Pillar project. The bonds will build a new high school that includes a vocational academy, where high school students can take Iowa Central Community College classes, including software development courses.

After finishing the Iowa Central software program, students—and anyone with skills, not just new graduates—can then apply to the Pillar Academy at the Jefferson Forge, just off the courthouse square. During the six- to eight-month training, students will work on real-world projects for nonprofits, Kroeger says.

While similar training costs at least $30,000, Pillar students will pay nothing. After completing the training, the students will continue at the Jefferson Forge as employees, with a starting salary of $55,000 to $60,000 a year. That jumps to $75,000 after a two-year apprenticeship, he says. By comparison, Greene County’s median household income was $47,264 in 2016 dollars, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“You have to invest more in this, and that’s OK. In tech, there is an extreme shortage of talent. We want to get them before they’ve left,” says Kroeger, who himself left Iowa after graduating from Independence High School in 1986.

He returned in 2015 to open Pillar’s Des Moines Forge. That office, across from the Pappajohn Sculpture Park, has 65 employees, about half from rural Iowa. That total exceeds the company’s commitment to the state to create 40 high-quality jobs in exchange for $200,000 in incentives, half of which came in the form of a 60-month loan.

Pillar hopes to hire 25 to 30 people at its new Forge eventually, and Kroeger even plans to woo Jefferson middle-schoolers. That project will include hands-on activities—“not just talk,” he stresses—and an extra effort to encourage girls to explore STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers.

“The idea is to get them engaged earlier,” he says. “Show them it’s fun.”