Image: State Historical Society of Iowa

Writer: David Elbert

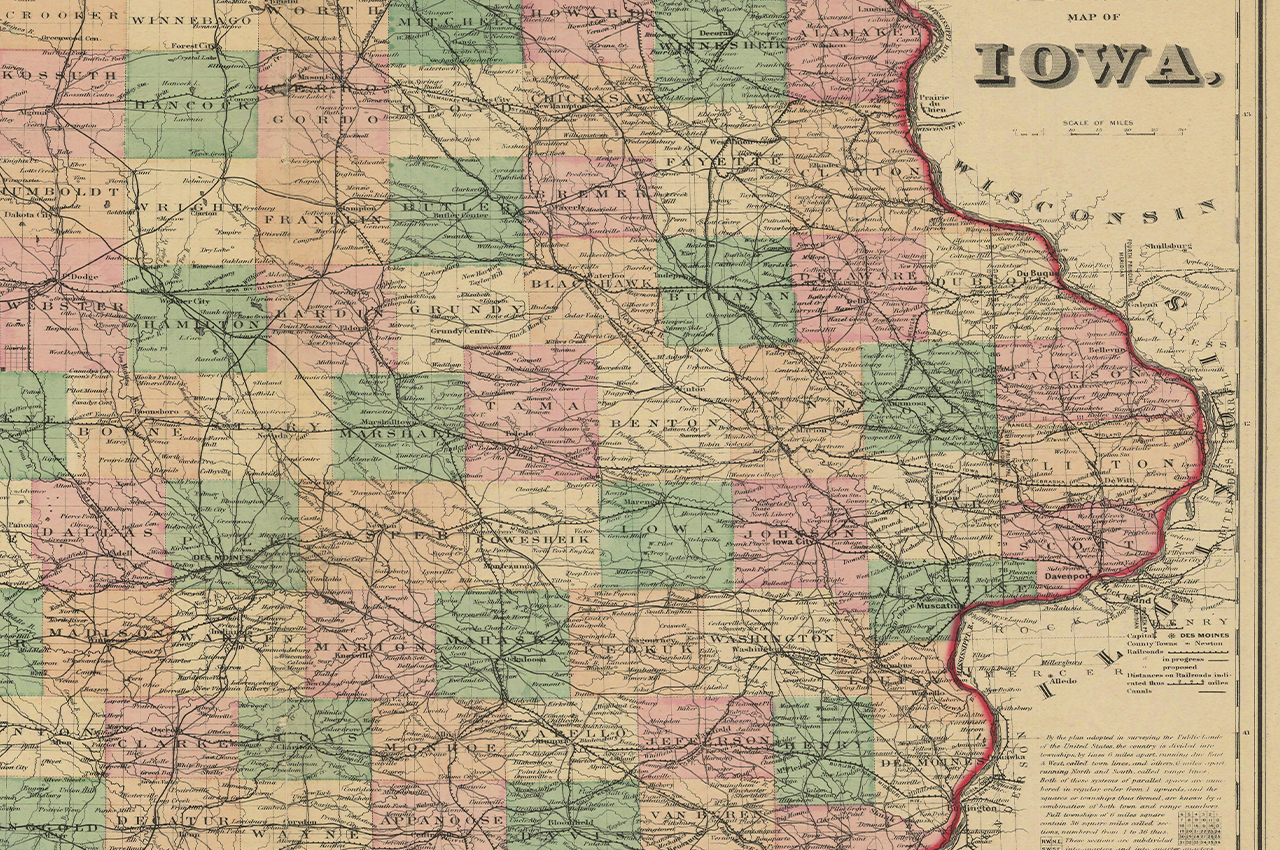

The names of Iowa’s 99 counties say a lot about its early decades, when surveyors trekked across the prairie to plot the tidy lines that literally put our state on the map. Early lawmakers chose county names to honor the usual who’s who of presidents, military leaders and Native Americans. But there are some surprises, too, including a few rebels, a princess or two, a birdwatcher, a meteorologist and possibly even a murderer. Turns out, our old county map is more colorful than you might expect.

For the most part, the shapes of Iowa’s 99 counties were drawn in the decades before and after Iowa became a state in 1846. The first two counties, Dubuque and Des Moines, were established on the Mississippi River in 1834. Five more counties in Iowa’s southeast corner were formed in 1836, and a few more riverside counties came along two years later. A real march to the west began in 1840, so by the time Iowa joined the Union, there were 29 active counties and plans for 15 more.

In 1851, the Iowa General Assembly created 48 new counties in one fell swoop, filling out most of the state map we know today. As a result, Iowa counties are among the most uniform in size and shape of any state in the country.

Even so, some of the names came later and switched over time. So, Iowa no longer has counties named Belknap, Buncombe, Crocker, Fox, Grimes, Kishkekosh, Risley, Slaughter, Wahkaw and Yell. Most of the former names had Native American connections or honored military leaders.

One notable adjustment in 1871 established Kossuth County as the state’s largest, with 973 square miles, twice the size of many counties. It swallowed up the former Bancroft County, which was named for George Bancroft, a historian and educator.

Much more recently, in 2021, Johnson County replaced its original namesake, a U.S. vice president who owned slaves in Kentucky, with a college professor named Lulu Merle Johnson, who was the first Black student to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa.

Here’s how the rest of the map filled in . . .

Presidents

In 1836, Martin Van Buren was elected to the White House and became the first of 11 U.S. presidents honored with an Iowa county name. That seems strange today because many historians rank Van Buren as one of the country’s worst chief executives. He had the misfortune of following Andrew Jackson, whose take-no-prisoners leadership effectively tanked the economy as Van Buren took office.

The following year, an Iowa county was named for Pennsylvania Sen. James Buchanan who helped establish the Wisconsin Territory in 1836 and from it, the Iowa Territory in 1838. He was elected president two decades later and often ranks even worse than Van Buren since his do-nothing style, the opposite of Jackson’s, led to the Civil War.

A pair of more popular presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, were added to the county map in 1839. But even then there was a twist: Washington was the second choice for a county already named after William Slaughter, the secretary of the Wisconsin Territory. Residents of the former Slaughter County had second thoughts about the sound of its name and chose to honor the president instead.

Women

As noted above, Johnson County chose a new namesake in 2021 to honor Lulu Merle Johnson, who was born in 1907 in southwest Iowa to a former slave and became in 1941 the first Black woman in Iowa to earn a Ph.D. and just the second Black woman in the country to earn a doctorate in history. She went on to teach at colleges in Florida and West Virginia, retired in 1971 as a university administrator in Pennsylvania and died in 1995.

The 2021 switch replaced the county’s original namesake, U.S. Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson, who owned slaves in Kentucky and claimed without proof to have killed Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1813. Those facts of the vice president’s biography didn’t sit well with today’s residents of the so-called “People’s Republic of Johnson County.”

Pocahontas, another county namesake, was born around 1596 to a Powhatan chief in what is now Virginia. She was 11 years old when Jamestown co-founder Capt. John Smith claimed that she had saved him from being killed by her father, although many historians now believe he misunderstood a welcome ceremony. Pocahontas was eventually captured, renamed Rebecca and forced to marry a colonist who took her to England where she died at the age of 20 or 21. She has no known connection to the northwest Iowa county and town that bear her name, but a 25-foot statue a local family built in the 1950s to honor her still stands today.

A less famous but more prolific county namesake was Fredrika Bremer, a Finnish-born writer and women’s rights advocate who grew up in Sweden. A patronizing sermon she heard in 1828 angered her enough to start writing anonymous “Sketches of Everyday Life,” which eventually grew into four books and launched her career as “the Swedish Jane Austin.” Inspired by Alexis de Tocqueville, Bremer toured the United States in 1848-1851 and visited several Scandinavian communities in the Midwest. At the time, the New York Herald suggested she had “more readers than any other female writer on the globe.”

There are two stories about the namesake of Louisa County, which was established in 1836. One suggests it borrowed its name from a Virginia county that was named for Princess Louise of Great Britain, who married a Danish king. A more visceral account traces the name to Louisa Massey, an early settler who infamously killed the man who murdered her brother.

Non-Americans

In addition to Bremer County and Fayette County, named for the Marquis de Lafayette, five other Iowa counties are named for people outside of the United States.

The most distinguished was Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian explorer, polymath and friend of Thomas Jefferson who influenced such writers as Charles Darwin, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He also invented isotherms, the lines of temperature and atmospheric pressure we see on today’s weather maps, and he was the first to explain how human activities affected the climate.

Humboldt County’s two northern neighbors were originally named Bancroft and Crooker. The boundaries of all three shifted later in the 1850s, and the two northern counties combined to form Kossuth County, named for Lajos Kossuth, whose failed efforts to establish a democracy in Hungary were widely supported and praised in the United States. His warm welcome in New York in 1851 was compared with earlier receptions for Washington and Lafayette.

Iowa’s three county namesakes from Ireland were from different factions of the war-torn island. Emmet County’s Robert Emmet came from a Protestant family who supported American independence. A gifted speaker, he led an unsuccessful anti-British rebellion in Dublin in 1803. He was captured and executed at age 25, but not before he gave a speech that echoed the one-life-to-give sentiments of 21-year-old Nathan Hale in the American Revolution. Emmet told his executioners, “I am here ready to die.”

Mitchel County’s John Mitchel was another Protestant nationalist who opposed British rule during the Irish potato famine. His journalism prompted his deportation to an island near Australia in 1848, but he escaped in 1853 and made his way to New York, where nativist hostility made him sympathetic to slavery. He channeled his writing talents to support the South during and after the Civil War, but his readership eventually dwindled and he returned to Ireland.

O’Brien County’s William Smith O’Brien was an Irish parliamentarian who encouraged the use of the Irish language. Like Mitchel, O’Brien was convicted of sedition, and he was sentenced to death in 1848. But petitions for clemency — from 70,000 people in Ireland and 10,000 in England — persuaded officials to exile him to Australia, where he was briefly reunited with Mitchel. After his eventual release, he returned home to Ireland but stayed out of politics for the rest of his life.

Native Americans

Including Pocahontas, 19 Iowa county names have Indigenous origins. The most prominent is Black Hawk, named for the Sauk chief associated with the Black Hawk War of 1832 in which he led raids from Iowa into Illinois. After surrendering, Black Hawk was taken to Washington, D.C., met with President Jackson, was imprisoned for a time and dictated his autobiography, which became a bestseller. He died at the age of 70 or 71 and was buried on the Des Moines River bank in Davis County.

Other counties named for Native American leaders are Appanoose, Keokuk, Mahaska, Osceola, Poweshiek, Wapello and Winneshiek. Indigenous nations are also represented in the counties of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscatine, Pottawattamie, Sac, Sioux, Tama and Winnebago.

Monona County takes its name from the Ho-Chunk or Winnebago word for “beautiful valley,” and Allamakee probably comes from a Sac/Fox word for “thunder.”

Geographical References

Six Iowa counties are named for geography. One is named for Delaware, the home state of U.S. Sen. John Clayton, who was an early advocate for the Iowa Territory. Another county is named after Plymouth, Massachusetts, where the Pilgrims landed in 1620. Union County was named in 1853 for the union of states that Iowans wanted to preserve in the run-up to the Civil War, and three counties are named for rivers — the Cedar, Des Moines and Iowa.

Speculation still surrounds the origin of the name Des Moines. Although one explanation points to a French term, “the monks,” there is no evidence that monks, French or otherwise, lived in the area. It’s more likely that Moines comes from Moingoana, the name of a Native American tribe that once lived in the area.

Des Moines Register writer Mary Challender added a layer of intrigue in 2003 when she wrote an article about a linguist’s theory that Moingoana originated from “mooylinkweena,” which translates, politely, to “the excrement-faces.” Another linguist took the theory a step further and surmised that when French explorers first arrived in 1673, Indigenous inhabitants welcomed them with a bit of ribald humor by explaining that the “Moingoana” lived up river.

Military Leaders

Although Iowa prides itself on feeding the world and famously hosted Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev on a peacemaking trip during the Cold War, more than a quarter of the state’s 99 county names honor military leaders. In addition to five presidential namesakes who were military leaders — Washington, Monroe, Jackson, Harrison and Taylor — 22 other county names have military origins.

That includes eight Revolutionary War generals: Nathanael Greene, Francis Marion, Richard Montgomery, Isaac Shelby, Joseph Warren, Anthony Wayne and the Marquis de Lafayette. A similar honor went to a brave sergeant, William Jasper, whose heroics were told, along with those of Sgt. John Newton, by the popular writer and truth-stretching historian known as Parson Weems.

Other military leaders whose names are now Iowa counties served in the War of 1812 — William Butler, Stephen Decatur, Winfield Scott and Williams Jenkins Worth. Similarly, the Black Hawk War involved Gen. John J. Hardin of Illinois as well as Gens. Henry Dodge and James Dougherty Henry, both of whom have ties to Henry County.

The Mexican-American War erupted eight months before Iowa became a state and inspired nine county names. That includes three battle sites (Buena Vista, Cerro Gordo and Palo Alto), three fallen soldiers (Frederick Mills, John Page and Samuel Ringgold) and three officers (Henry Clay Jr., Edwin B. Guthrie and John Charles Fremont, who later explored California and became the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, in 1856).

Even the Civil War, which broke out after Iowa’s county map was well established, gave us a county name. The first white settlers of the former Buncombe County decided to rename their northwestern county for Nathaniel Lyon, the first Union general to be killed in battle.

Politicians

Besides the presidents, 20 other politicians are county namesakes, including two vice presidents. John C. Calhoun served as vice president under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, and George Mifflin Dallas was President Polk’s vice president when Iowa joined the Union.

Four early Iowans were county eponyms, too, including territorial Govs. Robert Lucas and James Clarke, along with one of Iowa’s first two U.S. senators, George Wallace Jones, and William W. Hamilton, who presided over the Iowa Senate when Hamilton County was named in 1856.

A long parade of national politicians rounds out this category, in alphabetical order: Kentucky Gov. John Adair, Missouri Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, Michigan Gov. Lewis Cass, Delaware Sen. John M. Clayton, New York Gov. DeWitt Clinton, Georgia Sen. William Harris Crawford, Kentucky Sen. Garrett Davis, New York Sen. Daniel Stevens Dickinson, Tennessee Rep. Felix Grundy, Indiana Rep. Tighman Howard, Missouri Sen. Lewis Fields Linn, Massachusetts Sen. Daniel Webster and New Hampshire Gov. Levi Woodbury. Wright County is named for brothers Silas Wright and Joseph Albert Wright, who were respectively governors of New York and Indiana.

Others

Dubuque County honors Iowa’s first permanent white settler, Julien Dubuque.

Three counties take their distinguished names from men who signed the Declaration of Independence — Charles Carroll, Benjamin Franklin and John Hancock. And two other namesakes were U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, who helped elevate the court as a co-equal branch of government during his term from 1801 to 1835, and his colleague, associate justice Joseph Story.

Other Iowa counties bear the names of the artist and ornithologist John James Audubon, the early Iowa surveyor Nathan Boone (Daniel Boone’s youngest son) and U.S. Army Sgt. Charles Floyd, the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who died during the trip.

And finally, two county namesakes are unclear. Some believe Ida County is named for Mount Ida in Greece, while others point to Ida Smith, the first child born to immigrants in that part of northwest Iowa. In the opposite corner, the possibilities for Lee County include New York businessman William Lee, who sold land in Iowa; U.S. Dragoons topographer Albert Lea, who surveyed southern Minnesota and northern Iowa in 1835; and a young West Point graduate named Robert E. Lee, who joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and mapped the Des Moines Rapids near Keokuk in the 1820s, long before he made a name for himself in the Civil War.

Iowa County Eponyms

18 Native Americans

11 U.S. Presidents

3 Signers of the Declaration of Independence

20 Other Politicians

2 U.S. Supreme Court Justices

4 Women

24 Military Leaders

5 Non-Americans

6 Geographic References

6 Others

99 Total

Some categories overlap.